I often wonder why my phone sometimes dies fast and sometimes lasts all day. The battery seems magic, but the secret is inside.

Mobile phone batteries store energy in chemicals. When you charge your phone, these chemicals change and hold energy. That energy powers your phone until you use it up.

Now I will explain what’s inside a smartphone battery. I’ll show how the chemicals work, what stores energy, why some elements are used or swapped, and how layers of the battery are built. Keep reading — you may find the answer to many battery myths.

How do chemical components work?

I know the words “lithium‑ion” look scientific and a bit scary. But the working principle is plain once you break it down.

A battery works by moving ions between two electrodes. Lithium ions move from one electrode to the other during charge and go back when you use the battery.

When I plug in my phone, a charger pushes electrons into the negative electrode (anode). Meanwhile, lithium ions move through a thin fluid called electrolyte from the positive electrode (cathode) to the anode. Energy is stored because electrons and ions are separated: ions in the anode, electrons outside. The battery holds that difference.

When I later open an app or call someone, the circuit closes. Electrons travel back to the cathode through wires. At the same time, lithium ions move back through the electrolyte to combine with electrons at the cathode. That recombination releases energy. This process is reversible, so I can recharge many times.

The design uses chemical reactions that do not destroy the materials — they just shift ions and electrons. That lets the battery recharge again and again. The choice of chemicals matters. If reactions were destructive, battery life would drop fast. Instead, lithium‑ion chemistry gives high energy with good stability.

Because of this ion movement, batteries have limits. If you overcharge or discharge too fast, ions move too quickly. That can cause heat or damage internal layers. That is why proper charger and charging control matters.

In short: battery chemistry uses ion movement, separation of charge, and controlled reactions. That’s how batteries store energy and release it safely.

What materials store energy?

When I open a smartphone or see a battery teardown, the names of materials can sound strange. Yet each part has a simple role.

The key materials are lithium, graphite, and metal oxides. Lithium ions store and transfer energy. Graphite holds ions at one side. Metal oxides hold ions at the other side.

Inside most phone batteries, the anode is often made of graphite or a similar carbon-based material. Graphite has layers like sheets of paper. Lithium ions can slide between these sheets when the battery charges. The process is smooth and stable. Graphite is cheap and common, so most batteries use it.

The cathode is often made of metal oxides — materials that combine a metal like cobalt, nickel, manganese, or iron with oxygen. The metal oxide structure holds lithium ions when the battery is discharged. When charging, ions leave the cathode and move to the anode; when using the battery, they return. The choice of metal in the oxide matters a lot. It affects how much energy the battery can store and how stable it remains.

Electrolyte is another material. It is often a liquid (or gel) carrying lithium ions between anode and cathode. Its chemical makeup matters. It must allow lithium ions to move easily. At the same time, it must not react with electrodes incorrectly. Battery makers often use lithium salts dissolved in organic solvents. This mix keeps ions moving fast and helps battery last many charge cycles.

There is also a thin separator — a porous film that sits between anode and cathode. It lets ions pass but blocks electrons. Without a separator, the electrodes could touch directly and cause a short circuit. So it is very important for safety.

Here is a table summarizing the main materials and their job:

| Battery Part | Typical Material | Role in Energy Storage |

|---|---|---|

| Anode | Graphite (carbon-based) | Holds lithium ions when charged |

| Cathode | Metal oxides (e.g. LiCoO₂) | Releases or accepts lithium ions |

| Electrolyte | Lithium salts in solvent | Carries lithium ions between electrodes |

| Separator | Porous polymer film | Prevents short circuit; allows ion flow |

Together these parts store energy by moving and holding lithium ions. The materials matter — they decide how much energy fits and how stable the battery is over time.

Why use cobalt or alternatives?

People often ask why batteries use cobalt. I once wondered too. The answer is a mix of power, cost, and safety.

Cobalt in cathodes helps batteries hold more energy and stay stable. But makers now often reduce cobalt and replace it with nickel, manganese, or iron to cut cost and risks.

Cobalt in metal oxides offers good structure. When lithium ions leave during charging, the cathode must stay stable. Cobalt-based oxides handle the stress well. That means batteries with cobalt cathode tend to deliver high energy and longer life. That is why early lithium‑ion batteries used a lot of cobalt.

But cobalt has problems. It is expensive. Mining cobalt often raises ethical and environmental concerns. Some cobalt sources come from unstable regions, where labor conditions are poor. That makes reliance on cobalt less attractive.

Also, battery makers want higher energy for same weight. They found that materials like nickel or manganese — or combinations — can store similar energy or more. For example, nickel‑rich oxides can give higher capacity. Some chemistries mix nickel, manganese and cobalt in smaller shares (NMC) to balance energy, cost, and stability. Others use iron‑phosphate cathodes (LiFePO₄) that avoid cobalt entirely. Iron‑phosphate is safer and cheaper. It is more stable under heat or overcharge. It may store a bit less energy but offers long cycle life and safety.

Many newer batteries for phones or electric tools try to reduce cobalt or drop it. This lowers cost and environmental impact. It also reduces reliance on rare metals.

Here is a table comparing cobalt-based cathodes vs some alternatives:

| Cathode Type | Main Metals | Energy Density | Cost | Stability / Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High‑Cobalt Oxide (e.g. LiCoO₂) | Cobalt, Lithium, Oxygen | High | High | Good structure, decent safety |

| NMC (Nickel‑Manganese‑Cobalt) | Ni, Mn, Co, Li, O | Very High | Medium | Good balance of performance |

| Iron‑Phosphate (LiFePO₄) | Iron, Phosphate, Li, O | Moderate | Low | Very stable and safe |

| Nickel‑Rich Oxide variants | Ni heavy, some Mn/Co | High | Medium | Some tradeoff in safety/durability |

I believe in many cases, alternatives offer better trade‑offs than pure cobalt. They give good energy, lower cost, and sometimes safer batteries. That is why many makers choose them now.

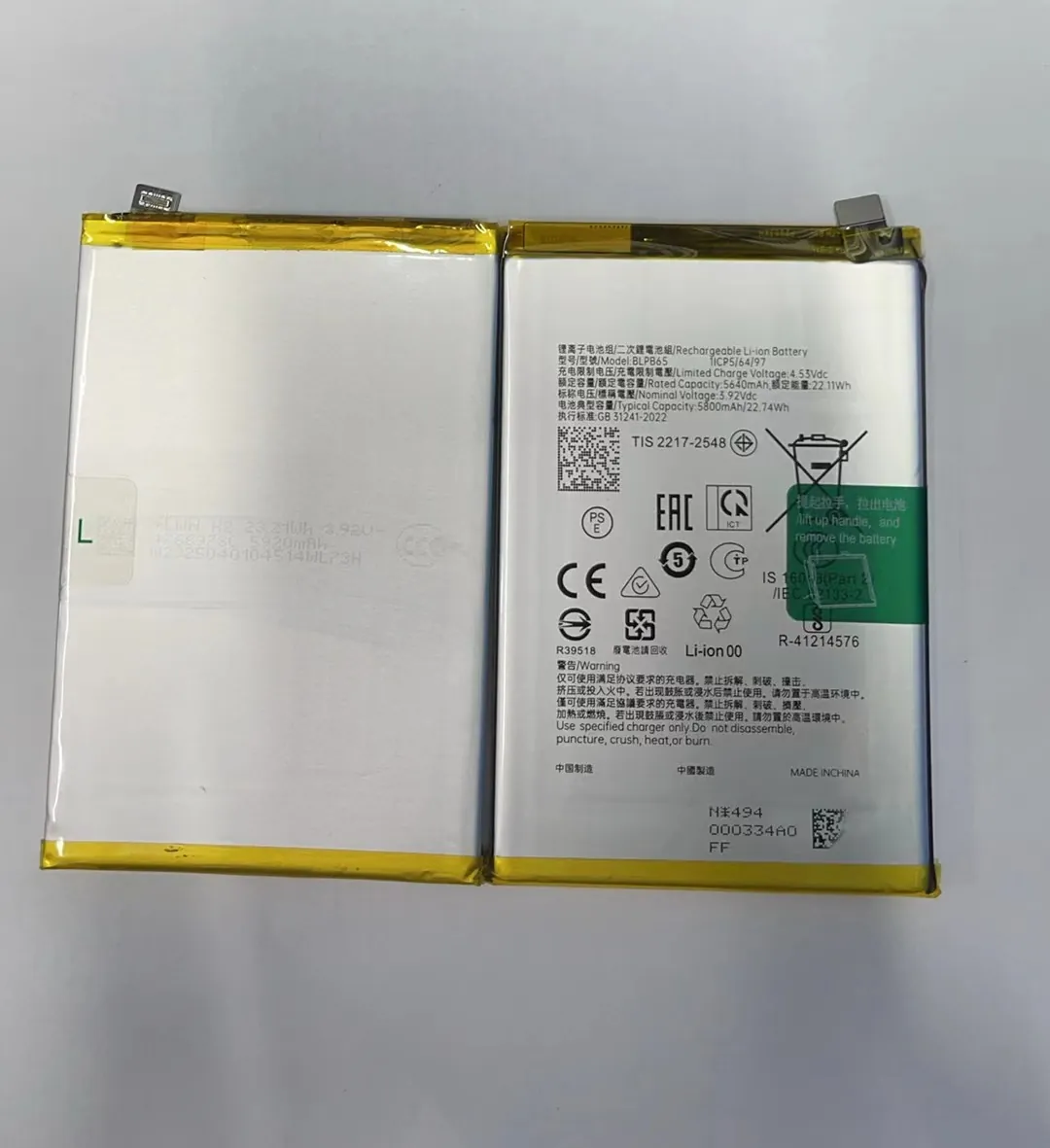

Which layers make battery structure?

Many people think a battery is just one piece. In real life a battery is like a thin sandwich of many layers. The layers all work together to store energy.

A typical phone battery has several layers: cathode layer, anode layer, separator layer, and protective outer layers. These layers stack in a tight pack.

Inside a lithium‑ion battery cell, layers are arranged in a stack or spiral (for “pouch” type batteries). First comes the cathode — a thin film of metal oxide coated on a metal foil (usually aluminum). That film holds lithium ions when the battery is discharged.

Next comes a thin separator — a porous plastic film. It touches the cathode foil, but it never lets electrons pass. It only lets ions pass through. That barrier is essential. Without it, the anode and cathode would touch and cause a short circuit.

Then comes the anode — a thin film of graphite coated on copper foil. That layer holds lithium ions when the battery is charged.

Around these internal layers there is electrolyte filling the spaces. The electrolyte is liquid or gel. It soaks into the separator and allows lithium ions to flow through when charging or discharging.

Finally, around all these layers there is an outer pouch or metal can. It seals the battery. This outer shell keeps everything tight, prevents leaks, and stops the entry of moisture or oxygen. Many phone batteries use a soft pouch made of layered plastic and foil. Others use hard metal cans.

Sometimes batteries add extra layers for safety or durability. For example a protection circuit board that monitors voltage and current. Or a heat shield layer to avoid overheating.

Here is a table to show the layer structure from inside to outside:

| Layer Position | Layer Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Innermost (cathode) | Metal‑oxide film on metal foil | Stores lithium ions when discharged |

| Separator | Porous polymer film | Prevents short circuit, allows ion flow |

| Anode | Graphite film on metal foil | Stores lithium ions when charged |

| Electrolyte filling | Liquid or gel electrolyte | Carries lithium ions between layers |

| Outer shell | Pouch or metal can | Seals battery; protects internal layers |

| Safety components | Circuit board, heat shield (optional) | Prevent overcharge, heat and overcurrent |

When I imagine the battery as a sandwich, each layer is a slice. The stack is compact. That compactness is important. Mobile phones need slim batteries. The thin films, foils, and pouch make it possible.

Because layers are thin, manufacturing requires precision. Even small impurity or defect can cause failure. Quality control must check every cell. If separator is damaged, battery can short. If cathode coating is uneven, capacity is lower. If electrolyte has unwanted water, battery may fail quickly. That means manufacturing matters as much as design.

I also note that pouch batteries are common in phones because they allow flexible shape. But they are more sensitive to puncture. Hard‑shell cells are stronger but thicker. For phone makers, pouch type gives best balance of size, weight, and safety.

Conclusion

I hope this gives clear view into what is inside a phone battery. Chemicals, materials, and layers all work together. Knowing this helps me and you understand battery life, quality, and safety.